Why is it important?

Electric and Electronic Equipment (EEE) (1) are a peculiar product: their production, use and end-of-life disposal contaminate the environment and generate GHG (use of energy, chemicals and mining, hazardous components, etc.), and they contain rare, non-renewable metals that become scarce.

The worldwide production of Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE or e-waste) is increasing by 3 to 4% every year and has exceeded 57 million tons in 2021. (2) In addition to the increasing consumption of electronic products, the life span of these products is getting shorter.

In 2019, WEEE had a recycling rate of 42.5% in Europe, 11.7% in Asia and 0.9% in Africa. (3) Yet, some of those wastes contain precious recoverable metals. Furthermore, untreated WEEE are a threat to the environment and health due to the potential presence of heavy metals, pollution in landfills, and associated greenhouse gas emissions.

Why is e-waste a key issue for the aid sector?

Countries of operation often lack an appropriate waste management system and, when they do exist, these systems can be overwhelmed or neutralised in a crisis situation. Some countries have proper legislation but not always enforced.

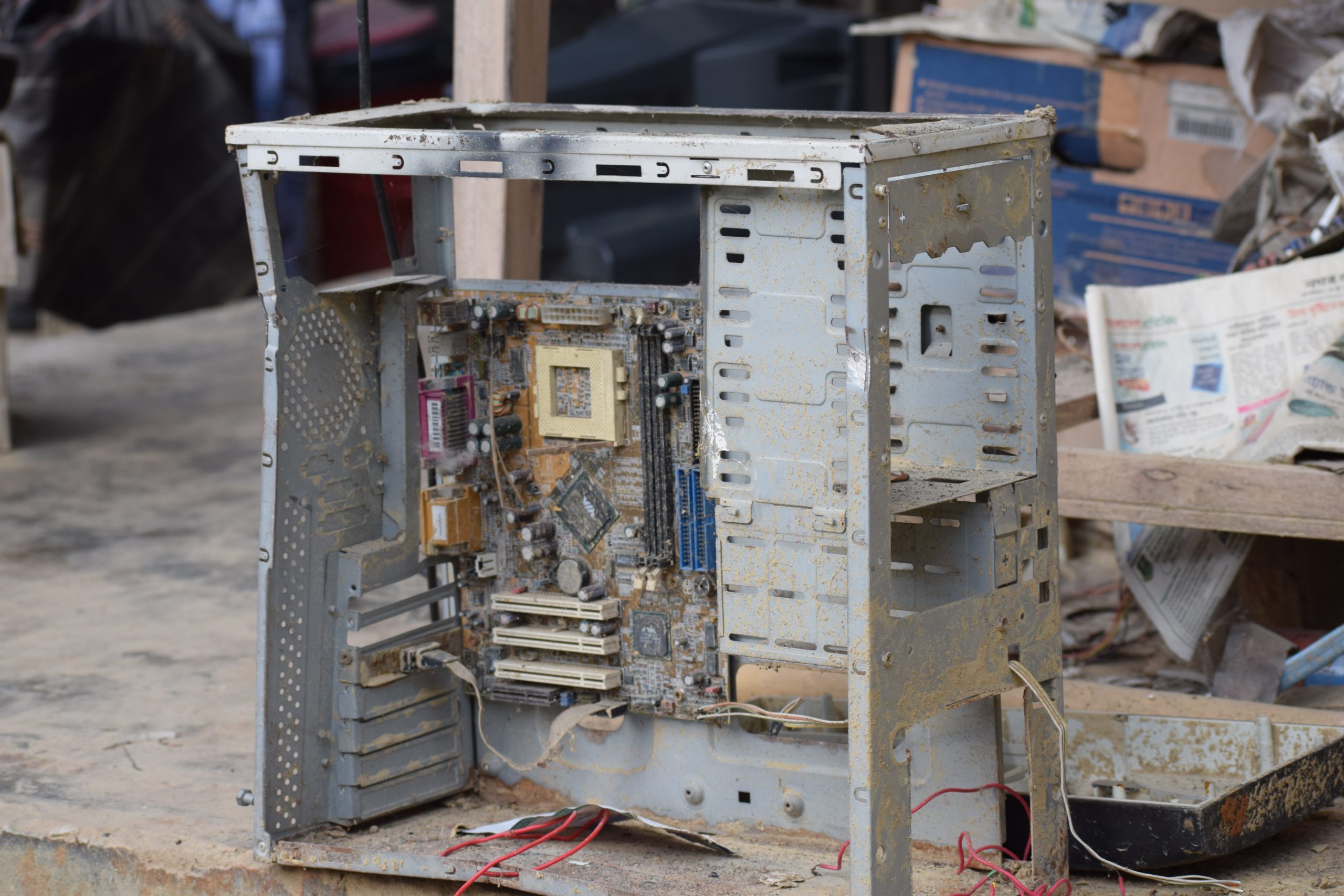

In developing countries, waste is mostly dumped in open landfills or incinerated, without much triage process. When they are not burnt or buried, WEEE are sometimes recycled in an artisanal way without any precautions for people or the environment.

The aid sector uses a lot of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) such as computers, mobile phones, air conditioners, printers, solar panels and batteries, refrigerators, televisions for the most common. The vast majority of this equipment ends its life in the field of operation and is not properly managed.

Key solutions

-

#1 Monitor, plan, and inform

The proper management of WEEE will require prior monitoring and planning. Monitoring consists of measurement work that will enable to size and plan activities and flows. Planning should consider the human, material and financial resources needed for the sustainable management of WEEE and the existing local resources and capacities. While the positive effects of reducing e-waste will remain barely visible at the scale of the organisation, it is important to value the progress and share measurable objectives to spread motivation throughout the staff, technicians and users.

An organisation can:

- Implement WEEE monitoring, including recording of the volume and type of waste generated.

- Identify the resources needed to implement proper WEEE management.

- Ensure traceability of WEEE (e.g., Waste Tracking Form).

- Identify local or regional recycling and treatment facilities. Seek public and private partnerships.

- Mutualise and join forces with other organisations and project-holders sharing the same issues. Capitalise and share information (on needs, local facilities, transport) and help each other’s.

- Ensure a technological watch on equipment (less energy-consuming, less polluting, more repairable).

- Train the relevant staff to choose, maintain and repair equipment, and manage the e-waste.

- Communicate on the efforts and results.

-

#2 Refuse and reduce

Refuse unnecessary or superficial devices and packaging. Reduce purchases of new or high consumption equipment. The best-managed waste is the waste you do not produce: make sure you buy the right, needed equipment, in the right quantity, and prefer products which produce as little waste as possible.

An organisation can:

- Avoid inappropriate or useless purchases. Assess electronic needs and ensure the devices purchased cover a real need (usefulness of 5g phones, touchscreen laptops or numerous screens).

- Share equipment as much as possible with others (cold chain, printers, flex offices).

- Do not replace equipment as long as it is functional or repairable (even for a less polluting one).

- Procure in priority secondhand reconditioned equipment.

- For new purchases, select long-life equipment, the greenest (ecolabels, certifications, low-tech, produced with recycled materials), easily repairable or modular.

- Standardise equipment as much as possible in order to develop specific expertise for technical support, and stocks of consumables or spare parts.

- Refuse unnecessary packaging, reduce harmful and wasteful products, request reusable or returnable containers.

-

#3 Maintain, repair, and reuse

Appropriate use, regular maintenance and repair extend the lifespan of devices and reduces the production of WEEE. The re-use of equipment, internally or externally (donations), makes it possible to extend the life of equipment.

An organisation can:

- Standardise procedures for use, maintenance, and life cycle management. Carry out preventive and corrective maintenance.

- Raise staff awareness on stakes and best practice in the use of electronic equipment. Create factsheets or manuals if necessary.

- Develop skills to assess whether a device should be discarded or repaired. Develop skills and repair workshops, or use external ones.

- Recondition (cleaning, upgrading) and reuse for same purpose. Identify reconditioning companies in the region of intervention.

- Share information with others, assess and mutualise transport to reconditioning companies.

-

#4 Repurpose

Aging electronic devices can be used for lesser purpose before considering being disposed.

An organisation can:

- Reuse computers whose power is no longer adequate for less demanding uses (meeting room computers, server).

- Make donations to local charities (schools or youth centers). Beware of donations to developing countries, which have little or no infrastructure for recycling and processing WEEE.

- Ensure the disposal of EEE donated to other users is agreed on and understood by informing beneficiaries about e-wastes stakes and risks.

-

#5 Sort and recycle

Proper and systematic sorting of WEEE is essential for subsequent treatment or recycling operations. Sorting should be carried out as early as possible in the waste production chain. Recycling avoids the need to mine, extract or produce again new raw materials.

An organisation can:

- Develop sorting rules according to existing disposal options. Train staff in these rules.

- Pre-sort the equipment by separating, if possible, the most sensitive components. Ensure safe handling of dangerous equipment.

- Implement sorting as close as possible to the place where the waste is produced.

- Check for and evaluate local recyclers (e.g., Weeecentre in Kenya). Some specialised companies recover rare metal from WEEE and sell them again as raw materials.

- Share information with others, develop and mutualise channels for transporting equipment to recycling companies.

- Support the development or maintenance of local recovery and recycling capacities (advocacy, join forces other organisations).

-

#6 Dispose

Elements that cannot be reduced, reused, or recycled will be disposed. WEEE must be treated in specific ways, considering the hazardousness or preciousness of each component and in partnership with local channels. Hazardous waste should be treated appropriately, locally if possible, or returned to suitable sites if necessary. The organisation’s responsibility is not limited to waste disposal: it is not enough to have a contract with an official waste disposal company, it is also necessary to know where the waste is going and how it will be disposed of.

An organisation can:

- Use locally available treatment and disposal channels. Establish partnerships. Support the development of local disposal capacities where needed.

- Capitalise and share information with others. Mutualise partnerships and contracts with other organisations sharing the same issues to make economies of scale (cost and GHG emissions).

- Ensure hazardous waste are decommissioned and dismantled in a responsible manner. Send hazardous waste that cannot be properly disposed locally to suitable sites (and share transport and contracts with others).

- Involve travelling staff to bring back a few kg of WEEE to countries with suitable channels (“Take a waste”). Caution: decision to be weighed according to the climate impact of the associated transport.

- Store waste that cannot be disposed of properly. Never allow your waste to be disposed of in illegal dumps.

Key points of attention

It is necessary to adopt a “life cycle” approach and to take into account the following essential stages:

- Needs assessment (to reduce quantity in use)

- Responsible procurement policy

- Operation (use and maintenance)

- Recycling, dismantling and disposal

Apply the Rs methods during the product life cycle:

- Refuse – no need to use it

- Reduce – use less of it

- Repair – make it usable again

- Reuse– use it again for the same purpose

- Repurpose – use it again for another purpose

- Recycle – transform and use its components again in other production cycle

Is it easy to implement?

As for other types of waste, the main difficulty, upstream, is to develop internal skills and capacities for procurement, responsible use and maintenance. This will extend the lifespan of an EEE item, and determine whether it should be disposed or repaired.

Downstream, i.e., when EEE become waste (WEEE), the main difficulty is the lack or deficiency of local waste management systems (recycling or disposal). Few interesting and the final sites of waste disposal are sometimes uneasy to access. In addition, having a contract with an official waste disposal company is not enough; it is important to know what they do with it.

To consider

-

Potential co-benefits

- Reduction of pollution

- Internal capacity and resilience building

- Creation of local jobs in repair, recycling, treatment

- Contribution to the local economy

- Acceleration and local strengthening of waste management legislation and capacities.

-

Conditions for success

- Mobilise and raise awareness among the staff on environmental issues, and educate them about the threats posed by WEEE to target populations, not only on the mid and long term (health, pollution and climate change), but also in the short term, with the frequent presence of acutely toxic substances

- Develop internal capacities (or involve external ones) in purchasing, maintenance, logistics (supply, transport, storage, etc.), environmental analysis and assessment of waste management channels

- Establish partnerships with other organisations in order to share equipment (cold chain, solar panels) and certain activities (maintenance, transport, sorting, collection, disposal)

- Define the acceptable cost of recycling and treatment of waste, especially the most hazardous waste

-

Prerequisites & specificities

- The waste management context will be very different from one region, country or even city to another

- Access to local recycling and disposal facilities

- Network of contacts with other organisation sharing the same issues locally

-

Potential risks

- Increased internal costs

- Increased complexity of internal processes

Food for thought

-

Food for thought

Sending secondhand devices for reuse in developing countries – as in Africa – is not necessarily a good idea from an environmental point of view, (unless the local capacity to manage their end of life is taken into account). Indeed, unlike in wealthier countries, there are few infrastructures for recycling and treatment of WEEE in developing countries, particularly in the least developed ones. Waste usually ends up in legal or illegal landfills, contributing to local environmental pollution and sometimes to additional health crises.

Good to know

Beyond the immediate danger that e-waste represents, the extraction of rare metals needed to produce our smartphones, computers, solar panels, lithium batteries and other connected objects is in itself a polluting industry. Major producing countries such as China and the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, are experiencing disastrous pollution and health issues in and around the mines. (8)

In addition to environmental and human stakes, the future shortage of precious metals contained in WEEE should encourage maximum recycling. Indeed, the price of nickel or lithium for electric batteries is rising sharply and some metals could soon face shortage (gallium, indium, yttrium, tantalum, etc.). Yet, these metals are present in many electronic waste products without being recycled or recovered. (9)

An estimated US$57 billion worth of recoverable materials were discarded or burned at the responsibility of producers in regions of the world without legislation. (10)

Tools and good practices

- World map of recycling companies, by Handicap International

-

QualiRépar Label

The QualiRépar label is aimed at both repairers, to integrate them into a professional network that enhances their value, and at consumers, to give them a reliable benchmark and incentive (in French)

Read here -

eeeasy! Staff awareness and training program

Educational modules, quizzes, workshops, communication materials. 1 hour of e-learning (3 modules of 20 minutes each) and/or 3 hours of face-to-face workshops (3 x 1 hour) to be organised in-house (in French)

Read here - Various resources for professionals: practical guides, signage, information kit (in French)

- Carbon impact of IT, audio and video equipment, ADEME (in French)

Recycling of electronic waste in various countries

To go further

-

Global e-waste monitoring

The Global E-waste Monitor 2020 presents the global e-waste challenge and explains how this challenge fits into international efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), create a circular economy and sustainable societies

Read here -

Waste management of aid actors

This study, carried out by Groupe URD and CEFREPADE, shows that Haiti has interesting recycling and recovery opportunities and reaffirms the importance of prevention and the choice of materials used in programmes (responsible purchasing), as well as the need to raise awareness of good practice internally (in French)

Read here -

Victims of electronic waste

In the suburbs of Accra, Ghana, there is a giant dumping field for computers, televisions and other computer equipment from developed countries (in French)

Read here -

Use of e-waste

Speeding up the recycling of e-waste is urgent because the extraction of precious metals is not sustainable

Read here

Digital

Waste management principles

Repairable items

Sources

(1) ‘Electrical and electronic equipment’ or ‘EEE’ means equipment which is dependent on electric currents or electromagnetic fields in order to work properly and equipment for the generation, transfer and measurement of such currents and fields and designed for use with a voltage rating not exceeding 1 000 volts for alternating current and 1 500 volts for direct current. Read here.

(2) WEEE Forum, “International E-Waste Day: 57.4M Tonnes Expected in 2021”. Read here.

(3) The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020. Read here.

(4) The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020. Read here.

(5) The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020. Read here.

(6) WEEE Forum, “International E-Waste Day: 57.4M Tonnes Expected in 2021”. Read here.

(7) The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020. Read here.

(8) Ideas4Development, “With rare metals, rich countries have outsourced pollution”, 2019. Read here.

(9) BBC, “Mine e-waste, not the Earth, say scientists”. Read here.

(10) WEEE Forum, “International E-Waste Day: 57.4M Tonnes Expected in 2021”. Read here.

(11) La Poste Groupe, “La deuxième vie des équipements électriques et électroniques du groupe La Poste”, 2021. In French. Read here.

(12) WEEE Centre. Visit their website here.

Cover photo © Set Sj/Unsplash.