Emissions gap has not narrowed

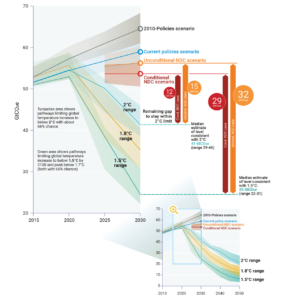

Just two days away from the Climate Ambition Summit co-chaired by Boris Johnson and Emmanuel Macron, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) revealed that the world is still heading for a temperature rise between 3.4 and 3.9°C this century under the current rhythm of emissions.

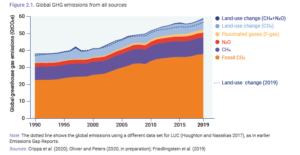

In its annual Emissions Gap Report 2020, the agency finds the gap has not narrowed compared with 2019 and is for the moment unaffected by the Covid-19 pandemic. Total greenhouse gas emissions reached a new high of 59.1 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent.

By 2030, annual emissions need to be 25 per cent lower (-15 GtCO2e) than current national contributions imply for a 2°C goal, and 50 per cent lower (-32 GtCO2e) for the 1.5°C goal.

However, Inger Andersen, UNEP’s executive director, insists that green recovery plans can still bring 2030 emissions close to levels needed for 2°C goal:

A green pandemic recovery can take a huge slice out of greenhouse gas emissions and help slow climate change. I urge governments to back a green recovery in the next stage of COVID-19 fiscal interventions and raise significantly their climate ambitions in 2021.

Why it matters

Postponed to next year, the United Nations climate summit, COP26, has been coined as the ‘last chance’ to fulfil the pledges of the Paris agreement signed in 2015. Five years later, the gulf between climate targets and reality has never appeared so wide. There is still no sign of inflexion in the curb of emissions and the world is geared towards catastrophic levels of temperature rise.

Hope comes from the 126 countries covering 51 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions that have adopted, announced or are considering net zero goals. But these recent pledges urgently need to be reflected in countries’ commitments under the Paris Agreement and backed with action. The levels of ambition in the Paris Agreement must be roughly tripled for the 2°C pathway and increased at least fivefold for the 1.5°C pathway.

Cassie Flynn, senior adviser on climate at the UN development programme (UNDP), which recently published new data (1) tracking the progress of 115 countries in achieving their climate promises, told Geneva Solutions:

This is very much a ‘red pill / blue pill’ moment – like in the film Matrix. The Covid pandemic has really sped up the conversation in countries, with recovery packages opening a window of opportunity for big bets on the future. But the transformation has to occur at a speed and scale unlike any other time in history, and high emitters must step up or it will affect the entire world.

Not yet a turning point

Each year, the Emissions Gap Report assesses the gap between anticipated emissions and levels consistent with the Paris agreement goals of limiting global warming this century to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°C. Here are the main findings of its 2020 edition:

- Although CO2 emissions will decrease in 2020, atmospheric concentrations of major greenhouse gases (CO2, methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O)) continued to increase in both 2019 and 2020.

- Pandemic-linked fall in 2020 emissions of up to seven per cent will have a negligible impact on climate change, translating into a 0.01°C reduction of global warming by 2050.

- Overall, we are heading for a world that is 3.2°C warmer by the end of this century, even with full implementation of unconditional nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris agreement.

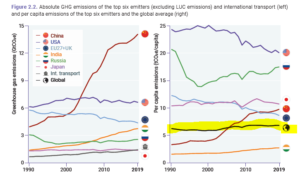

- There is some indication that the growth in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is slowing. GHG emissions are declining in Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies and increasing in non-OECD economies.

- Despite improving energy efficiency and increasing low-carbon sources, emissions continue to rise in countries with strong growth in energy use to meet development needs, notably China and India.

- As at October 2020, Covid-19 fiscal spending has primarily supported the global status quo of high carbon economic production or had neutral effects on GHG emissions.

So far, the opening for using fiscal rescue and recovery measures to stimulate the economy while simultaneously accelerating a low carbon transition has largely been missed. It is not too late to seize future opportunities, without which achieving the Paris agreement goals is likely to slip further out of reach.

Two thirds of emissions linked to private households

The authors underline the risk that the shipping and aviation sectors, which account for 5 per cent of global emissions, may consume between 60 and 220 per cent of allowable CO2 emissions by 2050 to limit temperature rise at 1.5°C. Notably if major efforts on energy efficiency and a rapid transition away from fossil fuel do not take place soon.

But as importantly, the report finds that stronger action must take place to change consumption behaviour by individuals and the private sector – by, for example, redesigning cities, making housing more efficient and promoting better, less wasteful diets. But also replacing domestic short haul flights with rail, incentives and infrastructure to enable cycling and car-sharing, improving the energy efficiency of housing and policies to reduce food waste.

Around two-thirds of global emissions are linked to private households, when using consumption-based accounting. The wealthy bear the greatest responsibility in this area. The combined emissions of the richest 1 per cent of the global population account for more than twice the combined emissions of the poorest 50 per cent.

This elite will need to reduce their footprint by a factor of 30 to stay in line with the Paris Agreement targets.

The bottomline

The Emissions Gap measures the gap between current policies and the effort to reach the climate targets approved in the Paris agreement. But it also exposes the alarming level of discrepancy between political commitments, national contributions as they stand today and implementation measures. Countries with high emissions per capita need to reduce faster – and the UK recently led the way by adopting a 68 per cent reduction target (2) by 2030 compared to 1990. Countries with high absolute level of emissions like China and India must also plan effectively their roadmap to carbon neutrality, and if not will continue to cancel the efforts made by others.

While the numbers may seem technical, what is really at stake here is the legitimacy of both internal and international political institutions and how they deliver on their promises. Should they continue to fail on the climate crisis in the decade to come, more radical political contestation by an angry youth may yet replace today’s peaceful demonstrations.