Why is it important?

The global food system is responsible for emitting 34% of the world’s greenhouse gases (1). The production of animal-based food (including livestock feed) accounts for 57% of these emissions (2). In addition to greenhouse gas emissions, the production of animal-based foods accounts for more than three-quarters of global agricultural land use (3) and consumes large quantities of water: 15,000 litres for 1kg of beef, 4,300 litres for 1 kg of chicken, as opposed to 320 l for 1 kg of vegetables (4). Between 2010 and 2050, additional global growth in demand for animal-based foods is projected to be 68 percent (3).

The recommended daily intake of proteins (animal or plant based) is on average about 60g per person per day for adults (5). Yet, the current worldwide average intake is 78.2 g per person per day, of which 33.3g come from animal origin (6). With a population of over 8 billion globally, this represents an overconsumption of more than 147,000 tons of protein every day. In addition, a high consumption of red meat increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases (7).

What is the solution?

Switching to a planetary health diet globally could reduce the projected food-generated emissions by 14% by 2050 and preserve planetary resources like water and biodiversity (8). The planetary health diet introduced by the EAT Lancet commission in 2019 recommends reducing the intake of foods such as red meat and sugar globally by 50% and doubling the consumption of plant-based foods such as fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes (9). It is important to note that the required changes differ by region, e.g. excessive meat consumption is mostly relevant for wealthier countries.

A planetary health plate consists of approximately half a plate of vegetables and fruits, the other half should consist primarily of whole grains, plant-based protein sources, unsaturated plant oils, and modest amounts of animal-based proteins. The recommendation is a weekly average of approximately 300 g of meat (including 100g red meat) and 500 g of pulses per person, and maximum of 3 meals per week based on animal proteins like eggs, meat, fish (9). See infobox on “What does a planetary health diet look like?”.

Reducing emissions from food consumption should be tackled holistically: Avoiding food waste as an important contributor to greenhouse gas emissions should also be prioritised, as well as using low energy cooking stoves or applying environmental procurement criteria such as purchasing low-carbon, local and seasonal food and reducing packaging.

This shift can be applied by aid organisations when designing general food distributions, as well as in canteens and cafeterias of companies, universities or hospitals. The change to a balanced and sustainable diet should be supported by initiatives aimed at increasing awareness and promoting understanding among staff, patients, students, and partners.

Examples of food‘s footprint

Examples of food‘s footprint (cradle-to-gate, i.e. covering the production, processing and packaging phase) (10)

- Beef meat (raw): 27.25 kgCO2e/Kg

- Red beans (dry): 0.95 kg CO2e/Kg

- Chicken breast: 6.53 kg CO2e/Kg

- Peas (raw): 0.43 CO2e/Kg

- Lentils: 0.66 CO2e/Kg

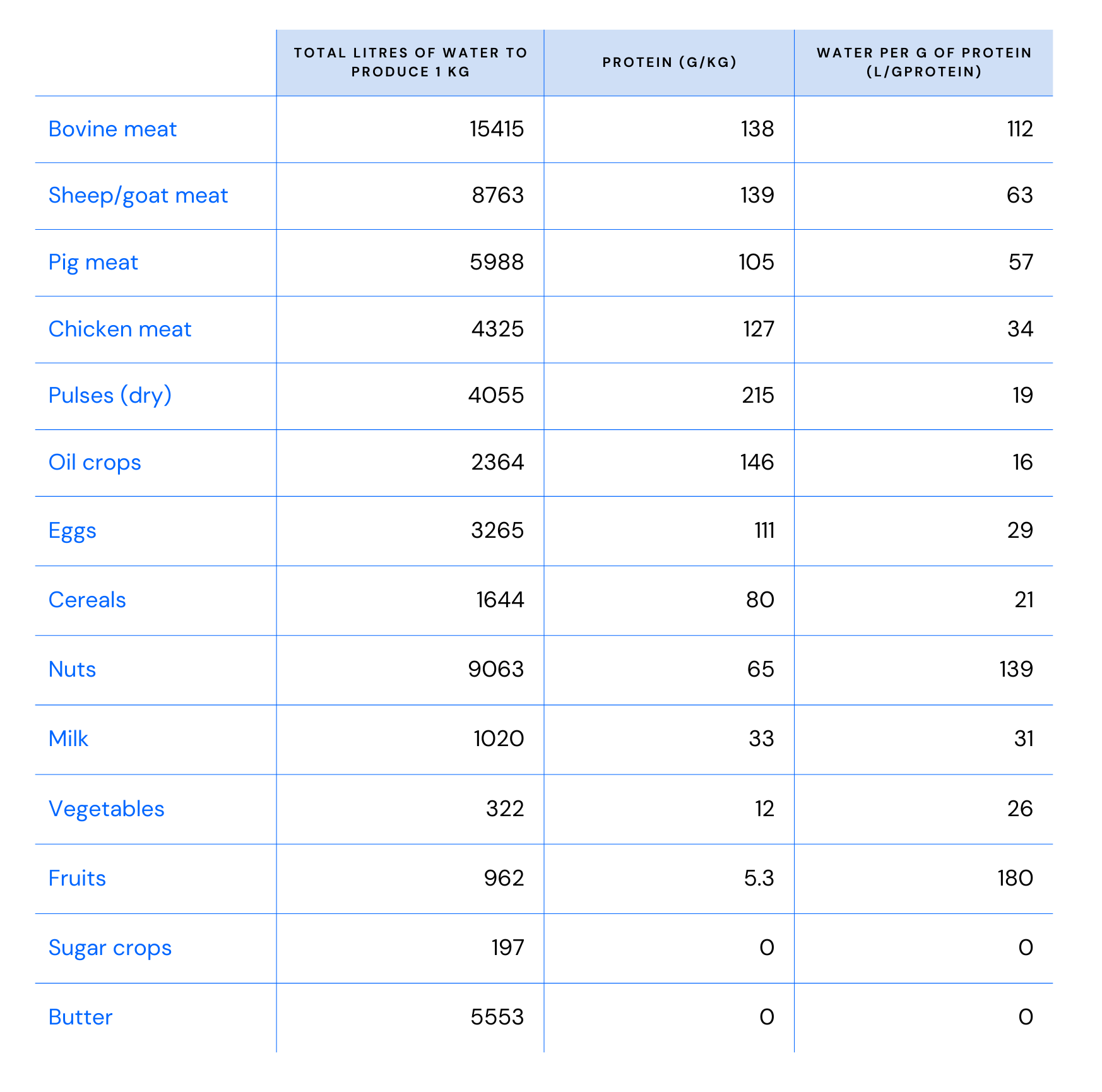

Examples of food’s protein content and water footprint

See reference (4)

Points of attention

-

Points of attention

- The planetary health diet provides suggestions for a change of global diets, these recommendations need to be adapted to local circumstances, habits and different nutritional needs (e.g. for young children, pregnant women, etc.)

- Specific contexts such as food aid require an adapted approach to implement healthy sustainable diets.

- The adoption of a planetary health diet would have positive health benefits, including reducing the intake of unhealthy saturated fats and increasing essential micronutrient intake (iron, zinc, folate, Vitamin A, etc.). (11)

- However, supplements or fortified foods may be needed to ensure adequate intake of vitamin B12 (11), even more so for people that choose a 100% vegetarian or vegan diet. (12)

- Plant-based diets may also include ultra-processed foods, such as cultured meat or yoghurt and cheese substitutes. There are significant knowledge gaps regarding the nutritional composition of these products as well as potential health impacts of food additives and by-products formed during industrial processes. (13)

Key actions

-

#1 Reduce meat consumption

Follow a planetary health diet: Reduce meat consumption and increase intake of plant-based proteins, like beans (dry or fresh), pulses (dry seeds), nuts, soy-based food, broccolis, etc. Refer to tools below for balanced menus and recipes.

-

#2 Limit other animal-based food

Follow a planetary health diet and switch from other animal-based food items (cheese, yoghurt, eggs) to plant-based options.

-

#3 Combine cereals with pulses or legumes

Ensure a healthy and balanced diet and combine pulses and other vegetarian proteins with cereals, vegetables and fruits. Avoid rice due to its high carbon impact and prefer other wholegrains cereals.

-

#4 Address other food-related issues

Reduce food waste, procure locally and seasonally, promote low-energy cooking and sustainable farming practices.

-

#5 Educate and raise awareness

Highlight diverse and culturally relevant recipes to encourage their integration into local diets. Create and launch campaigns aimed at raising awareness of the nutritional benefits of pulses. Consider partnering with relevant organisations in that area.

What does a planetary health diet look like?

The EAT-Lancet commission recommends the following average intake of plant-based foods per person (9):

- 232g of whole grains / day

- 50g of tubers or starchy vegetables / day

- 300g of vegetables / day

- 200g of fruits / day

- 75g of legumes / day

- 50g of nuts / day

- 40g of unsaturated oils / day

- 11.8 g of saturated oils / day

- 31g of added sugars / day

The commission recommends the following maximum intake of animal-based food consumption:

- 98 g of red meat / week

- 203 g of poultry / week

- 196g of fish / week

- 250g of dairy foods / day

Comment

See the EAT Lancet Summary report for further background information.

To consider

-

Potential co-benefits

- Health benefits, notably lower risk of diet-related non-communicable diseases, e.g. diabetes, cancer, heart diseases.

- Cost savings due to lower purchase price of pulses and plant-based proteins as compared to meat.

- Long shelf life of pulses, without losing high nutritional value.

- Increased food security through a diversified diet.

-

Success conditions

- Considering cultural habits when changing menus (18).

- Raising awareness on positive health benefits of a planetary health diet.

-

Prerequisites

- Dry seeds require preparation technics such as soaking to avoid high energy consumption when cooking at household level and to improve human absorption.

-

Potential risks

- Resistance to change

- Digestion issues if pulses are not well prepared

Tools and good practices

-

EAT-Lancet Commission Brief for Healthcare Professionals

The brief presents the report’s key takeaways and the specific actions that healthcare professionals can take to contribute to the transformation of the food system.

Explore here -

Proteins contained in each plant

A list of plants and the quantity of proteins they contain.

Explore here -

Procurement standards for canteens

The document contains minimum standards for healthier and more sustainable food sourcing in canteens. Whilst the document is geared towards public canteens, the content is easily transferable to any type of canteen.

Explore here -

Recipes, Pulses World

A website with almost 400 recipes that include pulses.

Explore here -

Plant-based recipes for canteens, Interfel (in French)

The guide contains recipes for pulses, geared towards collective catering, as well as factsheets on different types of pulses.

Explore here -

FAO material for sensitisation campaigns

Information material, including infographics for awareness-raising campaigns on the positive impacts of pulses.

Explore here

To go further

-

Can the EAT-Lancet diet work for the Global South?

Article discussing the feasibility of applying the recommendations from the EAT-Lancet commission to countries in the global south.

Explore here -

Graphic on over- and under-consumption of food items per region

The daily diet is broken down by food type and compared with current average food intake in world regions, showcasing the need for a contextualised approach to changing diets.

Explore here -

Graphic: emissions per kg of selected food items

The graphic provides an overview of greenhouse gas emissions per kg of food item.

Explore here -

French database on impact of food items (in French)

The Ademe database lists over 2500 food products and provides information on their environmental impact, including greenhouse gas emissions.

Explore here -

Water footprint of food guide

The website provides information on the water footprint of different food items.

Explore here

Featured

Food items

Procurement

Sources

(1) EDGAR findings: Crippa M, Solazzo E, Guizzardi D, Monforti-Ferrario F, Tubiello FN, Leip A. Food Systems Are Responsible for a Third of Global Anthropogenic GHG Emissions. Nature Food [Internet]. Available here.

(2) Xu X, Sharma P, Shu S, Lin TS, Ciais P, Tubiello FN, et al. Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Animal-based Foods are Twice Those of plant-based Foods. Nature Food. 2021 Sep 1;2(9):724–32. Available here.

(3) WRI. Creating a sustainable food future. A Menu of Solutions to Feed Nearly 10 Billion People by 2050 [Internet]. 2019. Available here.

(4) Mekonnen M, Hoekstra A. Value of Water Research Report Series No. 48 Volume 1: Main Report Value of Water [Internet]. 2010. Available here.

(5) Rust NA, Ridding L, Ward C, Clark B, Kehoe L, Dora M, et al. How to transition to reduced-meat diets that benefit people and the planet. Science of The Total Environment [Internet]. 2020 May;718(718):137208. Available here.

(6) Reedy J, Cudhea F, Shi P, Zhang J, Onopa J, Miller V, et al. Global Intakes of Total Protein and Sub-types; Findings from the 2015 Global Dietary Database (P10-050-19). Current Developments in Nutrition. 2019 Jun 1;3 (Supplement_1).

(7) Neacsu M, McBey D, Johnstone AM. Meat Reduction and Plant-Based Food. Sustainable Protein Sources. 2017;359–75. Available here.

(8) Nabuurs GJ, Aoki L, Ayala-Niño F, Emmet-Booth J, Nabuurs G-J, Mrabet R, et al. SPM 747 7 Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU) Coordinating Lead Authors: Contributing Authors: Chapter Scientists: of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P. GIEC [Internet]. 2022;Chapter 7(6th Report, WGIII). Available here.

(9) Food Planet Health Healthy Diets From Sustainable Food Systems [Internet]. 2019. Available here.

(10) AGRIBALYSE 3.1.1 – Détail par étape [Internet]. data.ademe.fr. 2022 [cited 2024 Apr 9]. Available here.

(11) Shepherd I. Five Questions on EAT-Lancet [Internet]. EAT. 2019 [cited 2024 Apr 9]. Available here.

(12) Niklewicz A, Smith AD, Smith A, Holzer A, Klein A, McCaddon A, et al. The importance of vitamin B12 for individuals choosing plant-based diets. European Journal of Nutrition [Internet]. 2022 Dec 5;62(3). Available here.

(13) Plant-based diets and their impact on health, sustainability and the environment A review of the evidence WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases [Internet]. 2021 Nov. Available here.

(14) Mbow, C., C. Rosenzweig, L.G. Barioni, T.G. Benton, M. Herrero, M. Krishnapillai, E. Liwenga, P. Pradhan, M.G. Rivera-Ferre, T. Sapkota, F.N. Tubiello, Y. Xu, 2019: Food Security. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Available here, see page 481.

(15) Searchinger, T. (2019). Creating a Sustainable Food Future: A Menu of Solutions to Feed Nearly 10 Billion People by 2050. Page 76. World Resources Institute. Available here.

(16) ECD/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2021), “Other products” and “meat”, in OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030, OECD Publishing, Paris. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/e1ed44a3-en

(17) Nabuurs GJ, Aoki L, Ayala-Niño F, Emmet-Booth J, Nabuurs G-J, Mrabet R, et al. SPM 747 7 Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU) Coordinating Lead Authors: Contributing Authors: Chapter Scientists: of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P. GIEC [Internet]. 2022;Chapter 7, p. 803 (6th Report, WGIII). Available here.

(18) Henn K, Bøye Olsen S, Goddyn H, Bredie Willingness to replace animal-based products with pulses among consumers in different European countries. Food Research International. 2022 Jul;157:111403. Available here.

Credits

Cover photo: Alesia Kozik/Pexels